|

In the sixth of an eight part series on the humble project management toolkit for better results in an uncertain world, I describe the second and third of the toolkit’s ‘compartments’ – “Understand the Project’s Ecosystem” and “Manage in Alignment with the Project’s Ecosystem” in which I outline the importance of developing adaptive management systems that take account of: the landscape in which the project is embedded; the project’s objectives and the processes implemented to contribute to these objectives; and organizational practices.

0 Comments

Why we need to overcome our negative bias and six ways to do itAll of you who are familiar with the Appreciative Inquiry approach to organisational, project and personal development will be aware of the following “Big Five” interlinked and overlapping principles that underpin the paradigm:

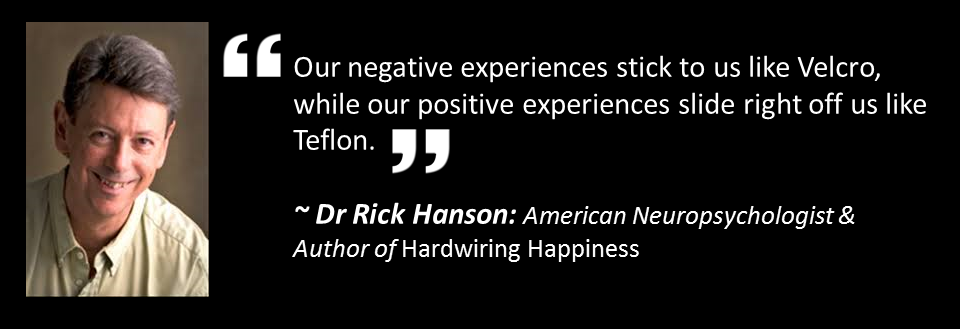

Why highlight the negative?What stands out like the proverbial sore thumb is my Principle No. 4 - We are programmed to pay attention to negative aspects of a situation. This does not conform to any of the principles I’ve seen in the AI literature. And without Principle 4 there is no need Principle 5, its antidote - We can override our programming by exercising our “appreciative muscles.” Given the fact that Principle 5 can neutralise Principle 4, what is the point of introducing Principle 4 in the first place? I believe that by highlighting the power of the negative we can provide a “safe space” in which to address those nagging doubts that many participants may harbour about AI. You know the sort of stuff that people feel and say – “this appreciative stuff is all very well but it won’t work in my [family, home, office, business, culture, country, etc.]”, “but sometimes we need to discuss bad stuff”, “I try to be positive but some things continue to wind me up” and most familiar of all “I’m not being negative, I’m just being realistic”. All of the above are justified sentiments, and I think we ignore such sentiments at our peril. Discussing them provides us with a valuable means of facilitating a new way of thinking in a manner that acknowledges the tenacious grip that “old paradigm thinking” holds on our individual and collective psyche. This helps the trainee to understand that negative feelings are reasonable though not always rational and that AI is a powerful way of addressing an inherent negative bias. Velcro and TeflonMost people are accustomed to problem-based paradigms. If you don’t believe me just watch any news bulletin for more than about a minute, consult most elementary psychology textbooks and find the non-existent or miniscule section on happiness, or leaf through any dictionary and count the numbers of words that describe positive versus negative emotions - according to one study seventy-four percent of the total words in the English language that describe personality traits are negative. Given this background, there is likely to be a degree of cynicism and resistance when Appreciative Inquiry is first introduced. Principle 4 acknowledges that a negative bias is the default setting for most people and groups. Even as a “born optimist” I know that this to be true. As Dr Rick Hanson, neuropsychologist and author of Hardwiring Happiness states “Our negative experiences stick to us like Velcro, while our positive experiences slide right off us like Teflon.” A typical example of this is my (internal) reaction to my children’s school grades. Even if most of the marks are high I am irresistibly drawn to the one or two lower grades. Of course as somebody versed in the art of “positive parenting” I would never give vent to the accompanying feelings of stress and urge to fix things but I feel these feelings nonetheless. Ok, if truth be told I probably do show these feelings more often than I should but at least I know that I shouldn’t! But ‘gut reactions’ such as those I describe above are the norm and are very deeply rooted for good reason. They have helped us and our ancestors to survive when our “nasty, brutish and short” lives were frequently subject to mortal dangers. Survival mode: keeps us alive - doesn’t help us to thriveWhy do we appear to be so irrationally negative? In a nutshell it is because of the evolutionary imperative to respond rapidly to danger – “survival mode” the familiar fight, flight or freeze response that allowed our ancestors to live long enough to become our ancestors. Nowadays the majority of us are not confronted by tigers as we go about our daily existence but our reactive response can be just as easily triggered by any number of “paper tigers” - perceived threats such as the audiences who question us, the bosses who appraise us, our offspring who disobey us, the spouse who ignores us, and even the anonymous drivers who disrespect us. Whether these perceptions are an accurate reflection of the intentions of these other people is immaterial. To paraphrase William Shakespeare’s Hamlet “there is nothing either stressful or not stressful, but thinking and feeling make it so.” Survival mode is manifested by the following physiological changes among others: elevated levels of the stress hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol (to prepare us to deal with sudden danger), raised breathing rate and blood pressure (to pump more oxygen around our body), increased perspiration (to prevent overheating), increased blood sugar (to boost energy where it is most needed), a reduction in the production of growth and sex hormones, a weakening of the immune system and decreased blood circulation to the digestive tract (to maximise resources available to deal with the immediate threat) and increased size and stickiness of platelets (to heal any wounds that might occur). These are great responses when our lives are under threat. But they do not stand us in good stead in the modern world when it comes to undertaking constructive everyday actions such as making decisions, collaborating with others, recalling information or having balanced discussions. The Antidote: Principle 4 -We can override our programming by exercising our “appreciative muscles”Setting the scene in this way helps to emphasise the fact that we shouldn’t beat ourselves up about our negative feelings - they are normal. I have always been a believer in the power of positive thinking but every silver lining has a cloud. My “positivity” has sometimes manifested itself as denial – a conscious effort to keep my subconscious mind and endocrine system in line (see my blog – Appreciative Inquiry - Denial by any other name. Denial of my own negative feelings could easily trap me in a double bind – feeling bad about some everyday thing and on top of that, feeling bad about the fact that I was feeling bad! An understanding of the evolutionary reasons for the reactive response can, at the very least, limit you to a single dose of bad feelings. Highlighting the fact that a negative viewpoint is simply one way of seeing the world allows us to question its usefulness to us in our day-to-day lives. Does it make for a positive work and home environment? Does it empower? Does it inspire? The answer to all these questions is likely to be something like “not in most cases.” The next question that comes to mind is “how can we address redress our negative bias?” This provides a platform upon which we can introduce a few of the growing number of approaches that we can use to shift us to a more positive outlook. But won’t this compromise our ability to go into survival mode when we are actually faced with a life or death situation? Assuming that you are able-bodies, you will do everything in your power to get out of the way as quickly as you can if are about to be run over by a bus, no matter how chilled out you most of the time. Millions of years of evolution will guarantee this even if you practice every positive thinking technique on the planet as long as you keep away from mind-altering drugs. In my introductory workshops I have highlighted the following six ways in which we can override our programming by building our “appreciative muscles”:

I examine each of these "muscle-building" approaches in my blog series on "Things I do… except when I don’t." ... (TIDEWID for short). 1. Asking empowering questionsI find all six approaches to be valuable and mutually supportive but only Number One, asking empowering questions, as part of the Appreciative Interview, is from the “Regulation Appreciative Inquiry Practitioners Toolkit”. There are plenty of excellent resources out there on how to conduct appreciative interviews, over ninety of which are listed in the AI Commons Practice Tools webpage: Positive Questions and Interview Guides. I highlight some empowering question fundamentals in my blog posting – Ask Empowering Questions: What Albert Einstein and Jeremy Paxman taught me. 2. Practicing gratitudeMy daily gratitude practice has helped me to appreciate the good times and to negotiate the inevitable tough times and I cannot recommend the practice too highly. I discuss the value of practising gratitude even for those situations which may appear to be unremittingly negative in my blog posting on the value of a daily gratitude practice - How I messed up my daily gratitude practice: Walking the tightrope between expressing appreciation and kidding ourselves. 3. Observing the thoughts that come to youObserving the thoughts that come to you is a method that allows you to disengage from disempowering thoughts so avoiding becoming enmeshed in those familiar spirals of negative thinking. I learned the technique from NLP and hypnotherapy expert, life coach and “head fixer” Ali Campbell who has stated that it is the single most powerful exercise he has done to improve his life. I outline this simple process in my blog on Decoupling Runaway Trains of Thought. 4. Cultivating stillnessThere are endless ways of cultivating stillness but a technique I particularly like is “Sixteen Seconds to Bliss” which I have adapted from the work of meditation teacher extraordinaire Davidji. I summarise this simple but powerful tool in my blog: Cultivating Stillness – Control, Alt, Delete for your Bodymind. 5. Embracing uncertaintyUncertainty pervades everybody’s lives and embracing it instead of fighting it helps allows us to view those inevitable “changes of a plan” as possibilities rather than roadblocks. In my blog posting – Embrace Uncertainty I outline some simple approaches I use for improving my relationship with uncertainty. 6. Being of serviceThe final way of building our “appreciative muscles I highlight in my introductory AI workshops is “being of service” – helping to make this world a better place. One rather dismal but widely held world view, a view upon which classical economics is founded, is that being selfish is in everybody’s best interest and it is competition alone that drives innovation and growth. This extreme form of social Darwinism ignores the fact that human beings must also collaborate to survive and thrive at every stage of their lives. To realise our full potential we must strive to be the best person we can be in the service of both ourselves and others. The universal truth of this viewpoint explains why we root for the heroes who fight for justice for all and against the villains who care only for their self-aggrandizement. I talk about how being of service can enhance your quality of life and outline ways in which you can maximise your contribution in my blog posting - Being of Service: Doing Well by doing Good. In Conclusion…I hope I have justified my “AI introduction with a negative twist.” Even if you disagree with the approach I hope that you will appreciate my intentions. The wonderful thing about the AI community is that it is a broad church with no concept of heresy; so nobody can ever be excommunicated! A little Postscript – EFT a seventh way to build your appreciative musclesIn my personal life I find Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT) or Tapping to be an excellent way of releasing negative emotions. Sometimes referred to as “psychological acupuncture”, EFT involves a sequence of gentle taps on acupuncture meridians or “tapping points” with your fingertips while talking through a particular issue of concern – a trauma, a phobia, a limiting belief or an ephemeral concern such as a looming deadline. I find that a few minutes of tapping rapidly reduces the intensity of my anxiety levels to near zero levels.

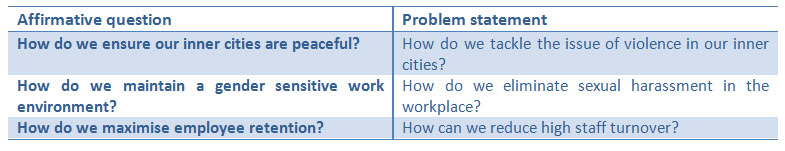

The jury is out on how exactly EFT works but there is a growing of evidence of its effectiveness. I do, however, have to confess a certain degree of bias as my lovely wife Julie Mauremootoo is a certified EFT practitioner. For the moment incorporating EFT into an Appreciative Inquiry workshop is likely to be a bit too radical for most of the folks I work with. However, I do foresee a time when EFT is incorporated into mainstream organisational development. Remember, you heard it here first! What Albert Einstein and Jeremy Paxman taught meWay back in May 2002 I was fortunate enough to receive an international conservation award. As a ‘reward’ I was interviewed about my team’s work by the famous British political broadcaster Jeremy Paxman. After swiftly dispensing with the niceties, he grilled me about the merit of the conservation work I was doing. I cannot remember the actual questions Paxman asked but my interpretation was that he wanted to trap me into confessing that the ‘conservation’ work I claimed to be doing was merely a front for something sinister like drug dealing, money laundering or international terrorism. Perhaps my interpretations have become a little exaggerated by the mutating effect of time but, whatever the case, I was unprepared for his abrupt and aggressive tone. Face to face with the inquisitor, I froze like a rabbit in the headlights and retreated into platitudes rather than revealing any deep insights about my work. Jeremy Paxman’s approach may have been effective in an adversarial arena where the objective is to expose half-truths but it was the bluntest of blunt instruments as a means of understanding the work I was doing. He lacked the empathy needed for situations where personal connection is more important than confrontation. Empowering questions – those that enhance connection and shared understanding, are the foundation of Appreciative Inquiry. Jeremy Paxman, no doubt, had many strengths but apparently, an appreciation of the value of the empowering question was not among them. The power of the questionWe will never know the answer but I would imagine that Albert Einstein would have used a different approach if he were to interview me. Einstein was the master of the art of finding the empowering question – simply defined as a question that helps you to get more of what you want and less of what you don’t want. In Einstein’s case the ‘more’ was powerful theories that could explain much of the physical world and the ‘less’ was blind alleys. The terms empowering question and appreciative inquiry are practically synonyms. The importance of empowering questions is enshrined in one of AI’s Big Five” principles, the Simultaneity Principle which states that inquiry is an intervention, systems move in the direction of the questions we most persistently ask, and change happens from the moment we begin our inquiry. In other words questions are extremely powerful so we need to make them count. Problematic questionsIn project management we traditionally base our planning on the “problem statement” – all the stuff that is going wrong that our project intends to fix. I have written quite a few of these problem statements over the years and they tend to go something like this:

But projects are essentially human systems, albeit involving mechanical processes to some extent. Simply stated, people don’t behave like cars. The problem-based approach, by emphasising what is going wrong discounts everything that is going right. Any good work that is being done may end up being devalued or simply ignored. This can easily be interpreted as personal criticism of those that have been doing this good work in the system under consideration. And on the whole people don’t respond too well to personal criticism. A “bright spots” approach, casting a spotlight on what is successful and why, helps to engender positive feelings and steer us towards the things that work. This can motivate us to ‘step up the stairs’, knowing that we are already part way along our journey. In contrast, focusing primarily on problems can paralyse us into ‘staring up the steps’ from a baseline situation that implicitly discounts any progress made to date. Turn that frown upside down - The Appreciative interviewThe whole AI process starts with the definition of an affirmative topic. Affirmative topics can be worded as questions such as:

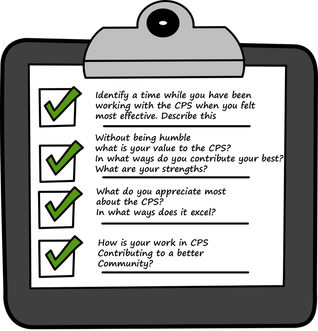

The appreciative interview usually covers the following areas: a positive experience relating to the issue under consideration, the feelings engendered by this experience, the actors and factors that contributed to this experience, the interviewee’s perceived strengths and those of the relevant entity (organisation, network, system, etc.) and their wishes which if granted could make their work and the relevant entity even more effective. The interview can be as long or short as necessary. Below are some commonly used appreciative interview questions: 1. Identify a time while you have been working with your organisation when you felt most effective.

3. What do you appreciate most about your organisation? In what ways does it excel? 4. Do you have three wishes that could help your organisation to become even more effective? As you will have no doubt have noticed, the “three wishes question” gives the interviewee scope to be critical as ‘wishes’ clearly relate to something that is currently not quite as you would like it. But it does so in a positive context. Paradoxically, the AI process can be a very effective way of identifying gaps that needed to be addressed as it facilitates honest disclosure in a non-judgemental environment. Tips for asking empowering questionsThere are many excellent guides on asking appreciative questions. Over ninety of these are listed in the AI Commons Practice Tools webpage: Positive Questions and Interview Guides. The due prominence given to the appreciative question is reflected in the titles of popular AI books such as Appreciative Team Building: Positive Questions to Bring Out the Best of Your Team, and Positive Family Dynamics: Appreciative Inquiry Questions to Bring Out the Best in Families. Here are some tips for asking empowering questions I have extracted from these resources and my personal experience: Questions are precious so use them wisely – Carefully plan your interview so that all your questions are asked with a clear purpose in mind to optimise the process. Establishing rapport is an important objective so you may need to spend some time on questions that appear unimportant to those with a western perspective on efficiency. Ask about what you want more of not what you want less of – Phrase questions positively as outlined in the section above on affirmative questions. Listen actively and without preconceptions so that you can capture the person’s perspective. Make the process personal to yourself and others. It is easier to imagine something when you can see yourself or people close to you being involved. Ask for personal experiences – “How did you feel when that happened?” “What gave you the strength to deal with that situation?” “What qualities did you observe in your team when you reached that milestone?” In this way you drill down to uncover inspirational stories and people relate to other people through stories. Use sensory language - Ask questions that activate the imagination using sensory language – daring to dream and “how would you feel if you achieved your goal?” and “what would success look like” questions help to turn up your senses in high definition. Be friendly not inquisitorial – One of the purposes of the interview is empowerment. It is not the Spanish Inquisition. I learned from my Jeremy Paxman experience that a wrathful question generates more heat than light. ReferencesDawn Cooperrider Dole, Jen Hetzel Silbert, and Ada Jo Mann (2008). Positive Family Dynamics: Appreciative Inquiry Questions to Bring Out the Best in Families Paperback. The Taos Institute Publications.

Diana Whitney, Amanda Trosten-Bloom, Jay Cherney and Ron Fry (2004). Appreciative Team Building: Positive Questions to Bring Out the Best of Your Team. iUniverse, Inc. New York, Lincoln, Shanghai. Tony Stoltzfus (2008). Coaching Questions: A Coach's Guide to Powerful Asking Skills. Pegasus Creative Arts. How I messed up my daily gratitude practice: Walking the tightrope between expressing appreciation and kidding yourselfI hope that my confession can help others avoid my schoolboy error so that they can tap into the power of an appreciative mindset. From Marcus Cicero to Marci Shimoff, countless thought leaders over many millennia have spoken of the power of gratitude. One way of cultivating Cicero’s “parent of all virtues” is a daily gratitude practice. There are a few variations on this theme but the practice essentially boils down to listing a number of things that you are grateful for each day. It is a tried and tested way of developing our “appreciative muscles” – creating new neural pathways and strengthening existing body-mind connections to change our perceptions; so that we see ourselves, others, and our world in a better light. Numerous studies have demonstrated the benefits of gratitude in terms of increased life expectancy, improved health and many other indicators of an enhanced quality of life. Some people explain the power of gratitude in terms of the law of attraction – your thoughts acting as magnets for life experiences; while others focus on the role of gratitude in shifting people from an unresourceful to a resourceful mental and physical state. Imagine, for instance, that your boss is unable to attend a meeting and they ask you, at short notice, to deliver a presentation in their place. If you are grateful for the opportunity you will be much more likely to benefit from the meeting than if you are resentful for the extra work load imposed. My wife Julie and I began our daily gratitude practice in April 2013 after Julie bought Jackie Kelm’s book, The Joy of Appreciative Living: Your 28-day Plan to Greater Happiness in 3 Incredibly Easy Steps. One of the steps is a daily gratitude practice in which you write down three things you are grateful for each day… Incredibly Easy??? Well... actually not very easy at all in my case. Pretty soon after starting the practice I was feeling considerably worse than I had felt before we had begun, which was obviously NOT the intended outcome!! Either something was wrong with the plan or the way in which I had been implementing it. Initially I was convinced that the plan was at fault but it soon became clear that I hadn't been doing it right. When listing my three gratitudes I had been focusing solely on the obviously positive things – the weather is nice, our children are healthy, we have enough to eat, etc., etc. - typical motherhood and apple pie stuff. However, both Julie and I had subconsciously steered clear of the “hidden gifts” that dwell in life’s more challenging situations. With each passing day I found myself smiling through gritted teeth as my feelings of dissatisfaction bubbled and churned beneath the surface. We were doing all this “appreciative” stuff but we were still massively in debt, my consultancy contracts had dried up and I was not in perfect health... but I felt that I couldn't talk about these subjects because that would be "unappreciative!" This culminated in me quitting the “charade” in a fit of petulance on Day 14 as I tried, and failed, to envisage my joy-filled life!! In one fell swoop I had consigned Appreciative Living to the “nice but not for me” category. I have to confess that I had not actually read Jackie’s book at this stage and Julie had only skimmed it, focusing mainly on Part Two “what you need to do” and not on Part One “what you need to know.”  Following my tantrum, Julie read the book from cover to cover in order to gain a fuller understanding of what Appreciative Living was actually all about. I was a bit reluctant to follow suit but Julie gently persuaded me to give the process a “fair trial.” In Part One Jackie explains, among other things, that every moment is replete with infinite possibilities and what we choose to focus on will become our experience – our map of reality. It was clear that gratitude actually means looking for the gifts in ALL situations; NOT drawing a veil over aspects of our lives that we wouldn't wish for in an ideal world - in other words not kidding ourselves. Armed with our new understanding, we restarted the practice in May 2013 and looked for the joy in all situations. It was challenging at first, but with training our “appreciative muscles” progressively strengthened. Our daily gratitudes are now a firmly ingrained habit and they have helped to turn our lives around. We are now out of debt, my health is improving and I am being hired for lots of exciting work … much of it using the principles of Appreciative Inquiry, the organisational development paradigm that inspired Appreciative Living!! The huge difference between gratitude and kidding ourselves was unclear to me back in April 2013 and my so-called “gratitude habit” actually ended up causing me more harm than good. Adopting an ostrich-like attitude to life’s challenges had left me vulnerable to some pretty powerful kicks in the rear end. But shining a light on the silver linings that dwell in every cloud, however small they appear to be at the time, has given me the strength to take action to deal with life's daily challenges as they arise rather than burying my head in the sand. So while it is great to appreciate things when they are going well, the gratitude practice really comes into its own when it is used to address life's setbacks; because the excrement of life can then be turned into rich compost and used as the most potent of fertilizers for our growth. ReferenceJackie Kelm (2008). The Joy of Appreciative Living: Your 28-Day Plan to Greater Happiness in 3 Incredibly Easy Steps. Tarcher/Penguin.

So that we can sort the wheat from the chaffCircular and repetitious trains of thought or jumping to confusions Apparently we have between 50,000 and 80,000 thoughts per day, that’s one thought every 1.2 seconds, which is a lot of thoughts. But of these thoughts, only about 2,000 are unique - still a lot of thoughts but also evidence that we are masters of recycling. As far as I know there is no collective noun for thoughts. For what it’s worth I think of a group of linked thoughts as a “train.” Unfortunately, in many cases our metaphorical trains of thought run away out of control, travelling in endless, pointless and frustrating circles that do not help us get to where we want to go in life. We’ve all been there. Somebody looks at you… you think he doesn’t like you… that’s because you’re too fat… because you eat too much… because you’re a slob… you eat because you’re bored at work… and your boss hates you, because you’re too fat… and so the train keeps hurtling along that well-beaten track to nowhere. I think therefore I have a thought: We are not slaves to our thoughts Many people’s perception of the power of thoughts is encapsulated in the famous Descartes' quote “I think therefore I am.” If we consider our thoughts to be our identity then we surrender our control over the translation of thoughts into feelings leading to actions and ultimately outcomes and impacts, part of the chain identified by Emerson in the opening quote. Descartes’ famous dictum can be profoundly dangerous if we take it to mean that everything we ever think somehow reflects our deepest selves. Taken to its logical conclusion, this means that we must be a mass of contradictions as all people’s thoughts and mindsets sometimes scale the heights of nobility while at other times plummet into the depths of banality or worse. The incontrovertible fact is that we are NOT our thoughts – if we were how would it be possible for us to step back and observe these thoughts? We observe our thoughts and let go of them much of the time because it is impossible to translate everything we think every day into feelings… there simply isn’t enough time. What I am proposing here is that we consciously cultivate our innate ability to observe our thoughts so that it becomes a habit that we can draw upon as and when we need it; thus enabling us to effectively decide which thoughts are useful to us and which ones can be discarded. Decoupling your trains of thought – breaking the link between a thought and a feelingOne way of achieving this is a pre-emptive strike, is by “getting into the gap” between thinking and feeling. There are many ways of doing this; one of which I outline in my blog Cultivating Stillness – Control, Alt, Delete for your Bodymind. Another technique I find really helpful, and which I outline here, was introduced to me by from Neuro-linguistic programming (NLP) expert, life coach and “head fixer” Ali Campbell. I call it decoupling your trains of thought. Ali describes this form of meditation “for people who suck at enlightenment!” as the single most powerful exercise he has done to improve his life… That statement certainly made me sit up and listen as it comes from a man who has a deep understanding of a rich smorgasbord of life-changing techniques. Below is a summary of this simple but very powerful exercise.

When you first start doing this you will probably find that the thoughts come thick and fast. Ali Campbell likens it to a dam bursting and unleashing a torrent of thoughts. But over time you will find that the thoughts flow more slowly, as if you are sitting by a river bank observing the thoughts gently flowing by. Once you have ingrained this practice into a habit you will know at the deepest level that you are not your thoughts. It is now clear that you are the observer of your thoughts. It is as if your thoughts are the trains that leave a busy station all night and all day. You are now free to decide which trains to take and when and where to take them. You no longer have to jump from train to train but are free to go where you want to go because you have the choice. ReferenceAli Campbell (2010). A Caring Compassionate Kick up the Arse. Hay House.

Control, Alt, Delete for your BodymindSurely nobody’s life is so frenetic that they can’t find just sixteen seconds a few times a day to recharge their batteries. Rebooting your system As detailed in the blog post Appreciative Inquiry and the Power of Negative Thinking… we are programmed by millions of years of evolution to go into fight or flight or “survival mode” when we feel that our emotional needs are not being met. One way to overcome this unresourceful state is to observe the thought. I outline a useful way of disengaging from your every thought in my blog post – Decoupling Runaway Trains of Thought. Another way, which I will discuss here, is to remember to breathe! Of course all of you reading this blog have been successfully breathing for your entire lives so this advice may seem a little pointless. Of course I don’t mean breathing in just any old fashion; what I am referring to is conscious slow and deep breathing... a skill that most of us do not cultivate. Witnessing your breath provides a wonderful pattern interrupt so that you can step out of the drama and emerge with a new sense of clarity. There are various breathing techniques that we can use for this emotional reboot. The simple practice I will describe here is based on the work of meditation teacher extraordinaire Davidji. He calls it Sixteen Seconds to Bliss. If 'Bliss' sounds a little New Age to you then feel free to call it Sixteen Seconds to Clarity. It is like a mini meditation for those who think that they cannot meditate or simply feel that they don’t have the time. Even those who do meditate every day can benefit from this short time-out when life’s day to day struggles appear to be overwhelming. Sixteen Seconds to Bliss While this is a great technique to use in stressful situations, initially it is best to practice it when you are in a calm, relatively quiet space. In this way you can ingrain the habit so that it is available to you when you need it most. All you need to do is follow these simple steps.

I doubt that you were able to maintain the stressful thought. In only sixteen seconds you can reduce your blood pressure, slow your pulse rate, suppresses stress hormones, elevate your growth and sex hormone levels, and bolster your immune system; and when practised regularly the effects last considerably beyond those sixteen seconds. Once it becomes a habit you can use this simple tool inconspicuously during most stressful situations, enabling you to step back from chaos and into a resourceful state. Of course it will not always be safe or convenient to close your eyes but the open-eyed version is also very effective. This technique can be used during a toilet break to great effect but for us guys I don’t recommend it while standing in front of the urinals! ReferenceDavidji. The Path to Bliss. Huffington Post Healthy Living (Accessed 7th February, 2014).

In so many spheres of life we are expected to provide definite answers rather than nuanced responses as illustrated by the bewildered response to the aid agency leader’s honest admission of uncertainty in the cartoon from Ben Ramaligam’s book. Politicians and preachers are experts in providing simple and clear solutions and this is what many people want to hear. Scientists don’t tend to talk in such a definitive manner. The nuanced tone of the scientific community is nowhere better illustrated than in the arena of climate change. 97% of climate scientists agree that climate warming trends over the past century are very likely due to human activities (emphasis added). Very likely is strong wording in the language of complexity science and I passionately feel that we should act on something that could be catastrophic in its effects and is very likely to be happening right now. However, very likely is not the same as certain and as long as there is some room for doubt there will always be people and organisations who are willing to exploit uncertainty as a basis for denial, inaction or the dissemination of deliberately misleading information. The fact is that uncertainty is the norm when addressing major questions such as how do we best combat terrorism?, how do we predict stock market performance? Is there one true God? Does God even exist? And which horse will win the 3:40 at Ascot? But our craving for certainty leaves us vulnerable to the charismatic pundits, priests and politicians who claim to have the definitive answers while we, the general public, lurch between competing certainties like some mortally wounded Shakespearian actor. So, I am going to throw my two cents into the uncertainty arena with my answer to the issue of uncertainty. There is no answer to uncertainty. Uncertainty was, is and will be with us forever so we had better learn to live with it and see it as a mystery to be embraced rather than a problem to be solved. In this blog I briefly outline why uncertainty is actually a good thing and then introduce some of the perspectives I have adopted to help me to embrace uncertainty in my everyday life. Tony Robbins identifies six conditions which must all be satisfied if we are to live a fulfilling life. He calls them the six human needs. They are:

Ideally all these needs should be satisfied but different people focus to different extents on different needs according to their personalities and the situations in which they find themselves. With regard to certainty and uncertainty, those who value certainty above all else are often known as prudent if you are focusing on the positive or control freaks if you are focusing on the downside; while those who crave uncertainty are known as daring at best and reckless at worst. In the context of Appreciative Inquiry I highlight the need to embrace uncertainty as one of six ways in which we can build our “appreciative muscles” in my blog Appreciative Inquiry and the Power of Negative Thinking. The reason I highlight the importance of this particular need is because uncertainty is ubiquitous, inevitable and increasing. The pace of change is growing with accelerating technological advances and globalisation. Slowly changing lifestyles and landscapes are becoming a thing of the past and our attitudes and behaviours need to adapt to this reality if we are to lead rounded and fulfilling lives. Here are six ways that have helped me to embrace a life of uncertainty: 1. Accept that change is inevitable and largely unpredictableA simple way to illustrate the unpredictability of the future is to contrast the consistently poor track record of pundits (those who predict specific outcomes - otherwise known as gamblers) with the healthy profits made by those who exploit this fact (those who play the odds – otherwise known as bookies). The following are a few nuggets from the plethora of famously flawed predictions made over the years. In 1876 Sir William Preece the then Chief Engineer of the British Post Office stated “The Americans have need of the telephone, but we do not. We have plenty of messenger boys.” At the time of writing there are probably as many cellphones as people on our planet… but not a commensurately huge number of messenger boys. In 1943 Thomas J. Watson the founder and long serving CEO of IBM stated “I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.” The average UK university student owned five computer or computer-like devices in 2015. In 2004 Bill Gates confidently asserted that “Spam will be a thing of the past in two years’ time.” Yet nine years later nearly 100 billion spam emails were sent... every day!!! These predictions have been cherry picked not only for fact that they were massively inaccurate but also because they were made by people who were at the top of their game in their respective fields. My objective is not to lampoon Preece, Watson and Gates but to illustrate that the much of the future is inherently unpredictable. I am sure that my predictions about telephones, computers and spam would have been no better if I had been in their shoes. Who could have predicted the fact that South Korea would now has a per capita GDP that is fourteen times higher than that of Ghana when both nation’s per capita GDP’s was $400 in 1957, the year Ghana became independent. Who could have predicted the legalisation of same-sex marriage in all 50 States of The USA by 2015 considering homosexuality was a criminal offence throughout the Union in 1961. And who could have predicted the rise of AFC Bournemouth from bankruptcy and rock bottom of the English Football League in 2008 to Premier League status in 2015. However, all of these developments, apparently impossible in foresight can be readily explained in hindsight. This fact, allied to our poor memories, the excuses we readily make for our failed predictions and the existence of the odd lucky or incredibly insightful individuals who actually make the occasional correct prediction (the punditry equivalents of lottery winners) contribute to the phenomenon known as hindsight bias which tricks us into confusing the explicability of the past with the predictability of the future. Hindsight bias is one of the reasons that we produce plans as if the future was certain and get upset when things fail to go according to plan. Planning becomes much simpler, and less frustrating, once we become aware of our poor predictive abilities in conditions of complexity. I outline ways of planning and managing projects and programmes under conditions of complexity in my Humble Project Management Toolkit talk. You can access it on YouTube but you will need a spare 45 minutes, or on SlideShare where you can scroll through it in ten minutes. The inevitability of change and its increasing rate, allied to our inability to accurately predict the future means that it is ever more important that we embrace uncertainty and do not become trapped by rigid preconceptions based on over-confident predictions of the future. 2. Develop a compelling vision_Being flexible and adaptable is not the same as being infinitely malleable and having no clear sense of direction. Despite the fact that the future is not predictable we still need to plan and have a system to help us to navigate the choppy waters through which we travel. An essential part of this navigation system is a compelling vision. There are many different and sometimes conflicting definitions of a vision. My definition (adapted from the Outcome Mapping approach to planning, monitoring and evaluation) is: A statement that reflects the large-scale changes to which you wish to contribute. It goes deeper than your personal objectives, is broader in scope, and is longer-term. The vision represents an ideal that you will support through your actions. I have a Personal Vision Statement that I periodically update in the light of experience. It can be found in my blog Being of Service: Doing well by Doing Good. Viktor Frankl, who is referred to in the opening quote, survived internship in four Nazi death camps including Auschwitz from 1942-45. His tenacious grip on life owed a great deal to his vision of humanity’s salvation through love and in love; a love he could access, even for a brief moment, when he contemplated the image of his wife. The fact that Frankl’s why helped to keep him alive and hopeful in the midst of such deprivation shows the value of a having a compelling vision through which you can find personal meaning in life, however dismal, confusing and unpredictable the circumstances may be. 3. Emphasise the journey above the destinationOur vision and objectives help to guide us but it is critical that we do not become attached to our intended outcomes above everything else. If we do so we run the risk of holding our happiness hostage to circumstances beyond our control. If we are fixated on an outcome we will tend to ignore, undervalue or marginalise unanticipated circumstances, events and outcomes as they unfold. In the words of evaluation guru Michael Quinn Patton, “being attentive along the journey is as important as, and critical to, arriving at a destination.” Most of our time will be spent on the journey and not at the destination so it is critical that we enjoy the ride or at the very least appreciate the lessons learned from the (inevitable) segments of the journey that are challenging at best and tragic at worst. This emphasis on the journey helps you to ground yourself in the present, the world as you find it rather than the world as you would like it to be. This mindful foundation empowers you to respond effectively to a constantly shifting personal and business environment. Tools to help keep you mindful along the journey include meditation (see my blogs Decoupling Runaway trains of thought and Cultivating Stillness) and a daily gratitude practice. Keeping a journal is another valuable tool. Journalling provides you with a safe place to vent. It also enhances your ability to reflect on events and reassess their meaning with the benefit of hindsight. Looking over my old journals tends to confirm H.G. Wells’s assertion that “The crisis of today is the joke of tomorrow." Journalling also helps us to recall what we did and when we did it with more precision than our memory usually permits – which can be useful when reporting to our bosses or resolving a dispute. I must confess that my journal or ‘daily log’ is very basic and restricted to the date, the event, and what category that event falls under – home, project work, football result, etc. - all entered on an Excel spreadsheet. I like to keep details of my work and home events in the same file. I also record “contextual events” such as football results and world events to provide additional hooks to assist my recall. My Excel spreadsheet is hardly evocative of the leather-bound, gilt-edged diaries of yesteryear but it works just fine for me. 4. Cultivate optimism tempered by hopeI am one of these annoying people who like to think they are a stickler for the correct terminology. If truth be told, I am a stickler for the correct use of the terminology that I am actually aware of and I have never taken much time to fathom the deep structures, rules and conventions of the English language. But I do know that the object in the wall that you plug your electric devices into is called a socket or a power point and not a plug. Perhaps I am overstating the case, but to me calling a socket a plug is analogous to calling a vagina a penis. And I wince when I hear people talk about there being less problems nowadays instead of the grammatically correct fewer problems (although I appreciate the sentiment behind the sentence in whatever way it is phrased). To be honest, these distinctions are not really important as communication is all about shared meaning. Less trivial errors are those that lead to fundamental misunderstandings that can have serious consequences. A possible example is contained in the famous sentence from the US Declaration of Independence statement as drafted by Thomas Jefferson to read “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” (emphasis added). Conventional wisdom equates the ‘pursuit’ of happiness with searching for or chasing after happiness. The implication is that you must chase after a lot of stuff in order to be happy. Taken to its extreme, the pursuit of happiness has been treated as being synonymous with the pursuit of wealth. However, there is a school of thought that believes that Jefferson was using the word ‘pursuit’ to mean an activity that you perform regularly or something you make a habit of. So if the latter interpretation is correct, Jefferson was exhorting the American people to practice happiness not to chase after it. It may seem like semantics but the implications of the two interpretations are profound. An important error, that only recently came to my attention, is the interchangeable use of the terms ‘hope’ and ‘optimism’ which could explain why optimists can be annoying while hope is often the more palatable virtue. Optimism and hope are closely related but they are not exactly the same thing. As Vaclav Havel implies, optimism is the conviction that will turn out well regardless of the situation. I happen to be an optimist of the incorrigible variety and do believe that positives can be found in even the most tragic of circumstances. However, I appreciate that not everybody thinks this and a (perhaps) more common view in the midst of difficult situations is that things could turn out well but they are not good now. There is a time dimension to this viewpoint. Things may turn out well but only after many years of struggling and, in my cosmology, many lives of hardship. Telling somebody that things are perfect when they have just lost their job, gone through a painful divorce or suffered a bereavement is not tactful and does not demonstrate a great deal of empathy. It is not surprising that people often rail against optimists because the truth is that bad things will continue to happen. If we deny this reality we risk suffocating those who are already suffering from a setback with a set of platitudes from the entire ‘Optimism Family’ – Incorrigible, Blind and Deluded. And we optimists wonder why our smiling faces are not always welcome when there’s grieving to be done, and that people turn their back on this ‘positive stuff’ when the going gets tough. Havel’s definition of hope accepts the reality that bad things will keep happening but that the resilience of the human condition can transcend these tragedies. In the words of David Henderson of the Center for Courage and Renewal “Hope will go toe-to-toe with reality because of a heart that simply refuses to quit. And there is no reality that can overcome the capacity of the human heart to withstand and even to ask boldly, Is that all you got? Is that the best you can do? My heart and the hearts of these people here with me are way bigger than that.” So while I remain an optimist, which is a valuable trait in the face of uncertainty, I strongly believe that hope should also be cultivated so that tragedy is given its proper due. 5. Abandon perfectionismI was brought up with the idea that perfectionism was a virtue. I would proudly proclaim that I was a perfectionist in job interviews, which probably explains my poor success rate in job interviews. At work I would agonise over every word in a report or every data point on a graph, checking and rechecking to ensure that I got everything right. In the meantime deadlines came and went, and by the time I finally submitted my report (which was always far from perfect in my opinion) it was often of scant value because much of its content had ceased to be relevant. As these perfectionism-related pitfalls persisted it slowly began to dawn on me perfectionism is a trap. Firstly perfection, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder and my perfect may be somebody else’s second best. Secondly perfect is not always appropriate. I found out about the 80/20 rule as applied to productivity – that 80% of your results come from 20% of your effort and the closer that you get to 100% the harder things become. And in many situations 80% or thereabouts might be good enough because the definition of quality is “fitness for purpose” not perfection. The bald truth is that perfectionists are unproductive. Despite these lessons it was still possible for me to “cheat” by working harder so that I would often go beyond ‘fit for purpose’ by putting in the ‘extra mile’ during evenings and weekends so I could (apparently) be efficient while approaching ‘perfection.’ This is not a recipe for a contented family life. I finally realised the folly of my ways when it dawned upon me that attaining perfection is an impossibility, because perfection does not actually exist beyond very narrow domains such as quizzes or examinations. I am somewhat ashamed that I was well into my fifth decade when I came to this simple but profound realisation. Having trained and practised as an evolutionary biologist I knew intellectually that natural selection does produce perfectly adapted species for many reasons including the fact that the landscape is always shifting. For example, the largest and strongest lion may be the best adapted when food is plentiful but his body size could be a handicap when food is scarce. And so it is in our work and personal lives - there are always trade-offs. Freeing yourself from the shackles of perfectionism is a way to embrace uncertainty as it liberates you from producing elaborate and excessively detailed plans when faced with complex situations though it should be used as an excuse for shoddy planning in predictable situations when a blueprint model is appropriate. 6. Don’t watch the newsCrime in England and Wales fell to a new record low in 2015, average life expectancy in Africa is at its highest levels in recorded history and worldwide it is the most peaceful time in our species’ existence (Pinker, 2011). So why does it feel like we are going to hell in a handbasket? I think that modern day news media and the fact that we consume it so uncritically bears a fair share of responsibility for this widespread perception.

Many people suggest that the news media should cover more positive stories. I agree with this perspective to some extent and pioneers like positivenews.org are helping to redress the news media’s negative bias. However, news by its very nature is sudden, dramatic and eye-catching and violent events such as a terrorist attacks, are inherently more newsworthy than incremental improvements such as the near elimination of smallpox from the planet. The understandable negative preference of the news media combined with our own negative programming (see my blog Appreciative Inquiry and the Power of Negative Thinking), and the fact that anybody with a cellphone and an Internet connection can be a news reporter helps to create an impression that we are embedded in a milieu of near-constant turmoil. The fact that most news reports concern situations over which we have very little influence contributes to our sense of insignificance. So what has all this got to do with embracing uncertainty? Many experiments have shown that willpower is a limited resource and negativity is one of the best ways to exhaust your willpower. If our senses are regularly assailed by tales of murder, disease, corruption, natural disasters and deprivation it is easily to view even day-to-day uncertainties as a source of stress against which we are impotent. And when we are short on willpower we lack creativity and resourcefulness and readily retreat into anger, apathy and cynicism. The good news is that the same global connectivity that serves up a diet of doom and despair is also a source of hope and empowerment – the story of Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani schoolgirl who stood up to the Taliban and the youngest ever Nobel Peace Laureate has spread around the world like wildfire, ideas once only available to an elite are disseminated to millions courtesy of TED Talks and people all over the world are getting access to the best teachers in the world thanks to free online learning resources. Becoming an active forager for information rather than a passive recipient helps us to achieve a resourceful state in which we can embrace uncertainty, not as something to be feared but as a source of our own empowerment. Doing well by Doing GoodThe "Secret" that launched a 1000 unfulfilled dreamsFrom self-help to personal empowermentI am a firm believer in self-help and the philosophy, mind, body and spirit books I have read over the years could fill the shelves of the personal development section of a medium-sized Waterstones. Nevertheless, I am uncomfortable with the self-help industry’s’ repeat billing formula; one that has a lot in common with the fitness and weight loss sectors – sectors which sustain themselves on failure. You know the syndrome: you buy the book, the DVD, the course and the all associated paraphernalia, begin the programme, abandon the programme, return to your rut, experience some kind of catalyst – a TV show, the Olympics, an encounter with the weighing scales, etc., and begin the whole self-defeating cycle all over again. So why does self-help fail so consistently? I believe that most self-help leaders are sincere individuals who genuinely want to help so I don’t think the repeat billing model is deliberate in most cases. There are other reasons including becoming discouraged by slow progress, comparing yourself to others, and setting unrealistic goals. However, my focus here is, I believe, more fundamental – a fundamental flaw in self-help is the excessive emphasis on the self in the first place, an emphasis that can descend into self-absorption and narcissism. Most people who have dipped their toes into the self-help waters will be aware of The Secret – available as a book, a movie and other spin-off products. The Secret’s author Rhonda Byrne claims to have brought to light the ‘law of attraction’ a secret hidden from the masses over the millennia that has inspired the success of the likes of Plato, Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo, Beethoven, and Einstein. In a nutshell, the ‘law of attraction’ or ‘manifestation’ states that if you visualise your goal you will achieve it. OK there is a bit more to it than that and I for one believe in the power of manifestation but I do not believe that manifestation is as easy as The Secret appears to imply. Byrne has recruited a veritable Who’s Who of self-help luminaries to testify about how they achieved wonderful relationships, perfect health, great wealth, palatial houses and a host of other objects of their desire through the law of attraction. To somewhat caricature the process, you can imagine manifestation as wishing for all the stuff you want in order to make you happy and then waiting for The Universe, which acts like a giant Argos store, to provide it for you – and without the need for in-store collection and self-assembly. All you need is a vision and an eternally optimistic outlook. There are a number of flaws with this approach. Firstly more stuff, beyond a certain level does not make people proportionately happier. Instead it just fuels the ‘hedonic treadmill’ – our habit of shifting the aspirational goalposts once an object of our desires has been attained. As Shawn Achor explains in his brilliant TEDx Talk – The Happy Secret to Better Work ‘You got good grades, now you have to get better grades, you got into a good school and after you get into a better one, you got a good job, now you have to get a better job, you hit your sales target, we're going to change it.’ Bruce Springsteen succinctly summarises the ultimate futility of life on the hedonic treadmill in Badlands when he sings “Poor man wanna be rich, rich man wanna be king, And a king ain't satisfied, till he rules everything…” Secondly, this emphasis on getting more and more stuff takes no account of the wishes of the other 7 billion plus inhabitants of our planet and even the planet itself. In the famous words of Mahatma Gandhi “The world has enough for everyone's need, but not enough for everyone's greed.” It is true that we can increase the production of goods and services and still reduce our impact on the planet by using resources more efficiently (so the proverbial cake can be expanded) but the earth’s cake is not infinitely expandable. Thirdly, The Secret fails to emphasise that we are social creatures - life is about we as well as me; and an emphasis on the self leaves us running the risk of excluding others from our life. We know from personal experience that helping others increases our happiness much more than pursuing a life of pure selfishness. This common sense observation that being of service enhances our quality of live is now backed up by a solid body of studies from the new science of behavioural economics which has demolished the myth, popularised by classic economists and their disciples (Margaret Thatcher springs to mind) who believe that most human interactions can be explained by ‘rational’ actions motivated by personal gain. The mantra of the bottom-liners is “everything must be paid for” and profit is their bottom line. But with a more rounded understanding of people’s needs and motivations comes the realisation that the profit motive alone is never enough (as if it ever was). So individuals and businesses are increasingly incorporating people, purpose and planet into a quadruple bottom line. This does not diminish the importance of profit but rather it weaves it into a richer tapestry. Reluctant though I am to quote Margaret Thatcher I do agree with her assertion that the “No-one would remember the Good Samaritan if he'd only had good intentions; he had money as well.” The quadruple bottom line reflects this as people are coming to appreciating that being of service does not mean you need to be broke. The mantra of the quadruple bottom-liners is “we can do well by doing good.” The importance of being of service has been emphasised by Tony Robins who lists contribution, along with certainty, uncertainty, significance, connection or love, and growth as the six human needs which must all be satisfied if we are to live a fulfilling life. Here are six ways that have helped me as I seek to live a life of service. 1. Know that we are all connected in the "Great Circle of Life"Part of the reason why a life of service is such a powerful force is that we are all connected – John Donne understood this, Jesus understood this when he said “Whatever you neglected to do unto one of these least of these, you neglected to do unto Me.” and Lao Tzu understood this in his conception of a force that flows through all life - The Tao. Poets and sages have long grasped the fact that there is no point at which the individual ends and the collective begins and physical, biological and social sciences are now catching up. In quantum physics Bell’s Theorem states that ‘entangled’ particles (those that once physically interacted when in close proximity) will somehow remain linked even if the physical distances between them are huge, implying that ‘communication’ is happening at speeds of greater than the speed of light. Less mystically ecology, systems theory and complexity science sees us as interconnected through a network of relationships so that the whole is more than simply the sum of the parts. Understanding that our individual ‘selves’ are merely abstractions from an interconnected reality helps us to empathise with ‘others’ because there are, in fact, no others. This helps when it comes to giving because giving is literally ‘self-service.’ Of course you cannot make an omelette without breaking an egg so not all interactions can be mutually beneficial. However, understanding that we are connected can at the very least prompt us to ensure that we do not over-exploit the resources upon which we depend and that we use free range eggs! This spirit of enlightened exploitation was eloquently expressed by Mufasa in Disney’s Lion King in his father-son conversation with young Simba:

2. Develop a clear vision and missionWe cannot just give at random and no one individual can constantly be available for the needs of the whole world. We are a drop in the ocean. But an ocean is made up of drops so if all of us can do our little bit then we can move mountains. But we need a clear focus if we are to contribute effectively to this mountain moving process. A personal vision and mission contribute to this focus and help us to prioritise the actions we need to take that will serve our vision and mission. A clear and compelling vision and mission makes it is easier for us to get out of bed every morning and do the right thing throughout our day. There are many alternative definitions of vision and mission. For me a vision is something bigger than ourselves to which we can contribute. My favourite all time ‘vision statement’ is Martin Luther King’s 1963 ‘I have a dream’ speech’ in which he outlines his vision for equal rights and justice for Americans of all colours. King knew that he might not live to see his vision become a reality and that he alone could not make it happen but he could and did make a powerful contribution to the vision through his life and his work. This personal contribution was King’s mission. There are many ways to develop an empowering vision and mission that will help you to use your skills and aptitudes to do good while doing well. I have used a hybrid of several processes to develop my personal vision and mission which I regularly update in the light of experience. This is my current vision and mission: Vision Project and programme planning and personal, professional and organisational development has been transformed through the use of flexible participatory approaches such as Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), Outcome Mapping, and Appreciative Inquiry. People throughout the world are able to effectively plan, monitor and evaluate their efforts in a manner that reflects the complexity of the real world and respects our planetary life support systems. i.e. People can implement participatory approaches to adaptive management to achieve significant, meaningful and environmentally sustainable outcomes. The widespread adoption of organisational development approaches based on the principles of systems science and positive psychology contributes to a world in which people are happy, healthy, connected to their environment and feel increasingly abundant because they are in a position to fulfil their potential. Misson Which issues do you intend to tackle?

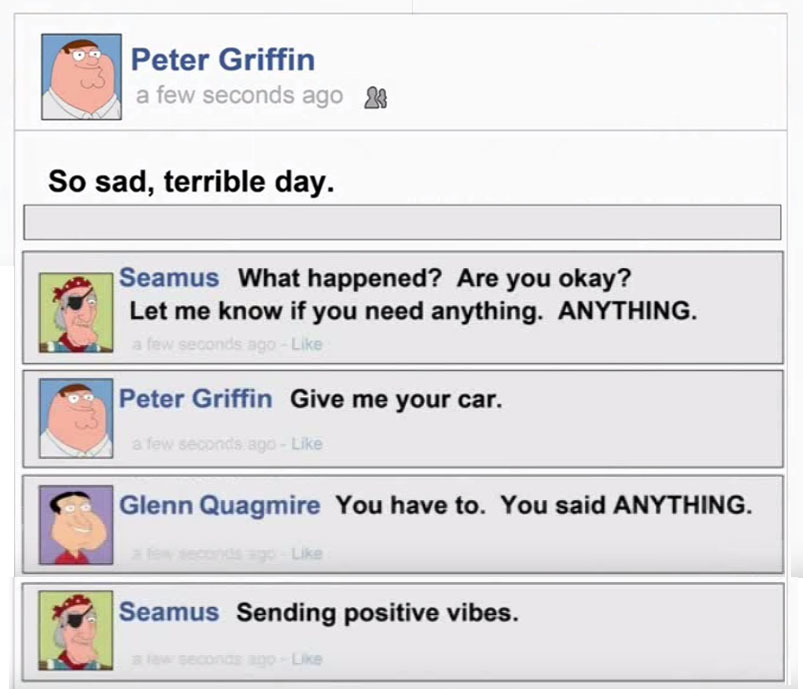

3. Serve your highest good and the highest good of all/ Look for win-winsI have already touched upon the fact that doing something for others is actually self-service. One way in which we can promote this ‘selfish altruism’ in our daily lives is by prompting us to stay alert for actions from which everybody benefits (win-wins). Other things being equal win-wins are much more likely to be profitable in the long term and sustainable than actions through which one party gains at the other’s expense (win-lose). We are used to competition in the sporting arena and for sport to be captivating there must be winners and losers. This assertion is supported by an observation that most people (particularly Americans in my experience) are perplexed by the game of cricket, in which a game can last for up to five days and still end up as a draw! Competition is also essential in life where resources are limited. However, in many cases it is possible to engineer outcomes that are mutually beneficial. Chip and Dan Hill in their excellent book Decisive: How to make better Choices in Life and Work outline the W-R-A-P framework as a method of guarding against overconfidence and making knee-jerk reactions when making important decisions. These rapid responses can result in decisions which are motivated from the perspective of narrow self-interest. W-R-A-P is an acronym for Widen your options, Reality-test your assumptions, Attain distance before deciding and Prepare to be wrong. Widening your options provides a rich hunting ground for win-wins. For example, instead of resigning if you are dissatisfied with your job you could examine the option of renegotiating your job description thus potentially helping yourself and your employer. Other examples of win-wins include profit sharing agreements between staff and business owners and customer loyalty bonuses. Many win-win situations mean that no single group gets 100% of the benefits of an interaction. For example there is a trade-off (at least in the short term) between profit and donations to good causes. So in many cases we will need to compromise on our short term individual objectives, something that does not always come easy to people raised to be (narrowly) competitive. This need to get 100% of what we want, just like the need to be right and the need for recognition, is fuelled by the ego which shouts ‘what about me’ which tends to ensure that it’s demands come to mind first when we are at the negotiating table. The Hill brothers’ advice to attain distance before deciding and to prepare to be wrong helps to provide the time, space and feedback to overcome the strident ego to improve the chances of us placing successful long term collaboration above short term gain. 4. Don’t over-promiseSeamus from Family Guy is not alone when it comes to overpromising… and then backtracking when the rubber hits the road. Over-promising and its partner over-giving can lead to burn out and resentment. We habitually over-promise in international development when we design short duration projects with highly ambitious objectives such as “the removal of barriers to protected area management in Country X”, “the implementation of a viable coral reef management system in Country Y”, and “the establishment of the conditions for sustainable urban rehabilitation in Country Z”. Then we get upset when our colleagues take us to task for failing to deliver on our promises. It is the same with training courses. Trainees invariably finish the course ready and eager to apply their new knowledge and skills to transform their lives and those around them. But upon re-entry our would-be World Changers are often faced with a less than enthusiastic reception from those back in mission control – the house needs cleaning, the kids need looking after and those deadlines are now even more urgent than they were when you left the everyday world behind. Simple stated, we cannot control all aspects of the environment in which our project operates nor what trainees actually do once the training course has been completed. So rather than promise the earth we can emphasise possibilities, and the fact that the project or training is only one among many factors that contribute to an outcome. This kind of bounded optimism – getting to maybe rather than getting to yes – is unlikely to resonate with those self-help gurus who ask us to eliminate words like “failure”, “doubt” and “impossible” from our vocabularies. But a diverse lexicon that permits different words in different contexts sits comfortably with somebody like me who recoils from fist-pumping, stage pyrotechnics and living my life to the accompaniment of anthemic rock music. 5. Find roles model or heroesOpinion is divided when it comes to the value of having heroes. Many people feel that putting anybody on a pedestal is a one way ticket to disappointment. But I believe that we can learn a great deal from people’s positive qualities while still being mindful to their imperfections. For me, a hero is an ordinary person who personifies specific virtues, and whose achievements in a particular sphere can inspire us to be the best that we can be in certain aspects of our lives. So I keep a heroes list to remind me of these qualities. Some of my heroes who exemplify being of service are Franklin D. Roosevelt for his practical concern for the poor, Wangari Maathai the Kenyan environmental activist for her courage to confront authority, Dame Cecily the founder of the hospice movement who valued the dignity of all lives and Viktor Frankl a Nazi concentration camp survivor and author of Man’s Search for Meaning who emphasised giving to others as a means of transcending our day-to-day concerns. Having such role models allows me to ask the questions about what would Franklin, Maathai, Cecily or Frankl have done or advised me to do when faced with daily situations. For me it provides a valuable tool to tap into the collective psyche. My heroes list currently stands at 111. It is steadily increasing although there is the occasional deletion. Lance Armstrong fell off the list a few years back, not because he no longer embodied certain heroic qualities but because it is hard for me to focus on these qualities in view of his years of lying and cheating. Perhaps I can ‘reinstate’ him once my abilities to forgive have matured. 6. Do something today – it will give you momentumLife is for living and to live it to the full you must become a participant. So the ultimate proof of being of service is how much you do to serve others and the best way to start is by doing something today. When embarking on a new habit it is best to start small and as outlined above, you don’t want to overpromise or over-give.

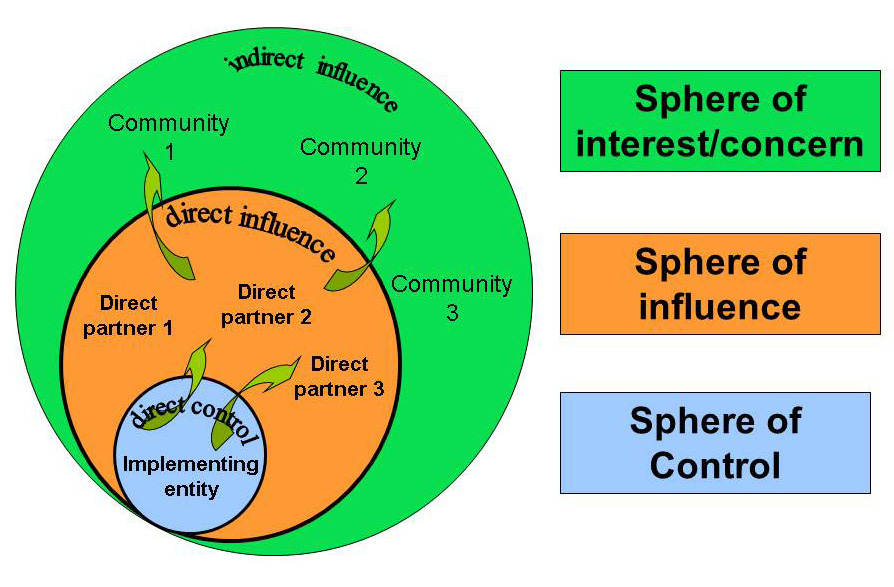

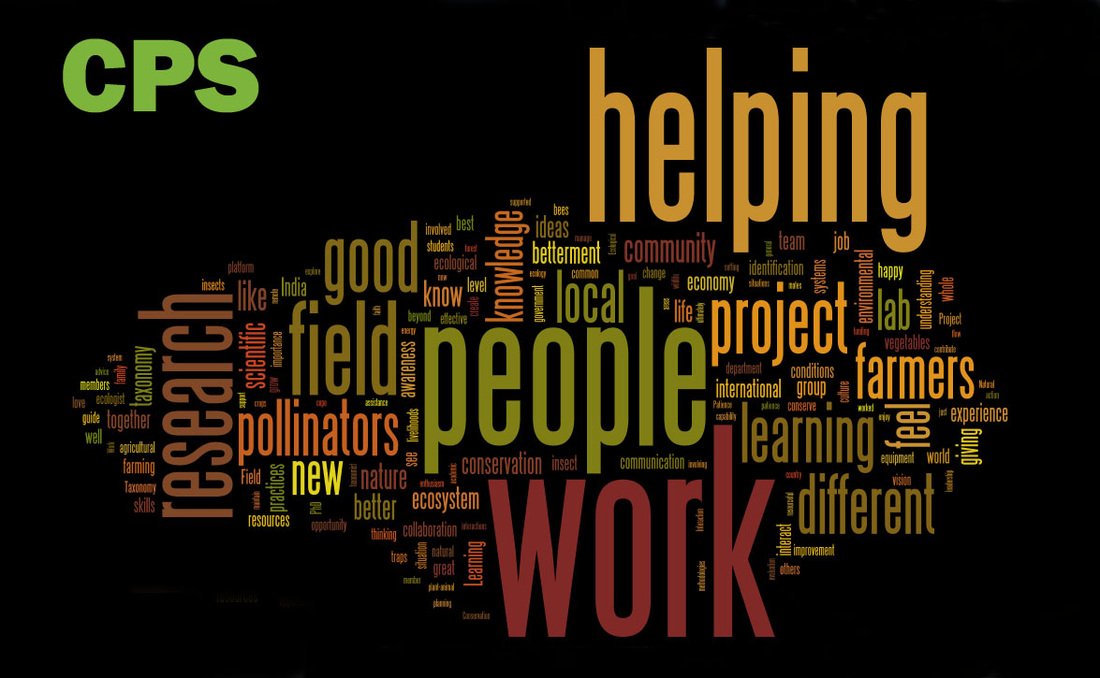

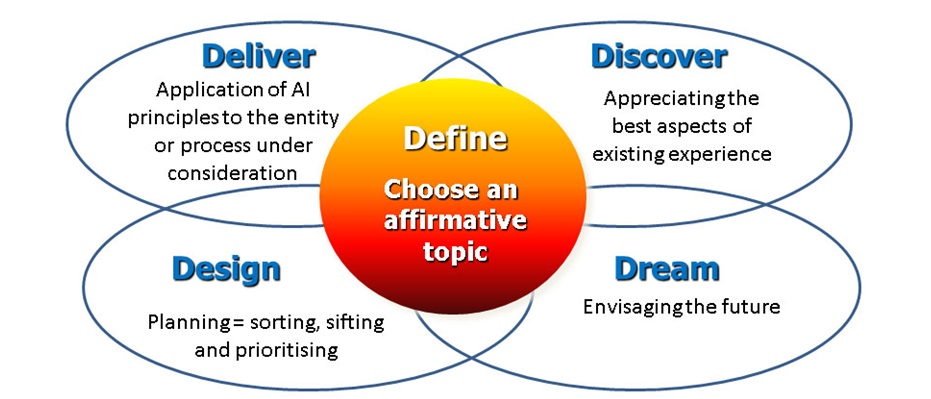

Small acts of kindness can be incorporated into your daily life without too much difficulty. Thanking people for their help is about as simple as it gets but this small gesture can help brighten up people’s day. Little complements cost nothing but can touch people’s hearts. We are often quick to criticise but we sometimes forget to praise. I spend a lot of time in airports and have recently adopted a systematic approach to helping those weaker than myself take their luggage off the airport baggage carousel (I do give their luggage back to them by the way!!). It is a small helpful gesture that gives me a lot of pleasure and costs me absolutely nothing. Whether it is being of service or any other sphere of life, you can’t steer a parked car. So get in gear, release the handbrake and get going. Images: Scared child by D Sharon Pruitt (CC BY-2.0.) and A peanut butter and jelly sandwich… (Public Domain) On Friday 4th of October 2013 I led a workshop to introduce Appreciative Inquiry (AI) to the Centre for Pollination Studies and Parthib Basu’s Ecological Research Unit in the Department of Zoology, University of Calcutta. AI is being used by Parthib’s group to help to enhance their learning, project planning, monitoring and evaluation and to banish practices based on that often unpalatable mix of positive and negative statements or questions sometimes known as “the complement sandwich.” The development of CPS’s participatory approach to planning, monitoring and evaluation It has been a pleasure to be able to work with the CPS team to help them develop their planning, monitoring and evaluation (PME) practices. In November 2012 we put together a PME system for the CPS based on the Project logical framework approach and Outcome mapping (OM). OM is a participatory PME approach that explicitly acknowledges the fact that any intervention is embedded in a complex reality comprising of multiple actors and factors, only some of which are under the control of the project or programme. For more details of OM’s 12-step process you can download the Outcome Mapping Facilitation Manual. If you want something shorter, a 4-page summary of OM can be downloaded from the Outcome Mapping Learning Community. OM’s focus is on a project or programme’s direct partners in its sphere of influence (those individuals or organisations with which the programme interacts directly and anticipates opportunities for change) as opposed to its spheres of control (those who work full-time for the programme), and concern (stakeholders who are still of interest to the programme but are beyond its direct influence). OM provides the “who” in the logical sequence between activities (what the project does) and outcomes (changes to which the project contributes). Stakeholder Circles: A programme cannot control change, it can only influence and contribute to changes at the level of its direct partners

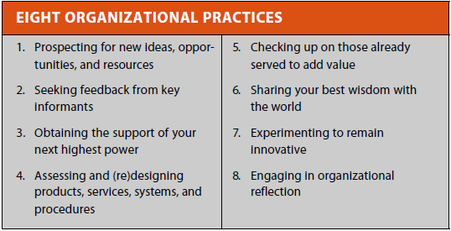

Given time constraints we did not look at the CPS organisational practices when developing the PME system in November 2012 but we all agreed it was an important issue which we needed to address at some point. I was keen but somehow the step as outlined in the OM manual didn’t entirely resonate with me. My concern was that without careful planning we could inadvertently use the eight practices as a rope of (k)nots with which to beat those in the organisation: what we are not doing to prospecting for new ideas, what we are not doing to share our best wisdom with the world, what we are not doing to remain innovative, etc. My fears may have been unjustified but my mind kept conjuring up images of the stereotypical employee performance appraisal interview. I am sure that everyone is familiar with the bitter taste left by the “compliment sandwich”, a critical comment or question between two positives, that is invariably served up on such occasions. What if there was a method of organising such reviews which ensured that the tasty bread in the sandwich was not tainted by a noxious filling while at the same time not producing something bland or sickly sweet? Appreciative Inquiry to the rescue Step forward Appreciative Inquiry (AI), an organisational development paradigm that focuses on what is working to generate more of what you want instead of concentrating on what is broken in order to fix it. In our meeting in November 2012, we felt that AI could be the ideal vehicle to address CPS’s organisational practices - by building upon the already substantial strengths and achievements of the group. The first thing to establish was whether AI was right for the CPS. This we did through a three hour workshop in which I introduced the principles of AI to the Ecological Research Unit. You can download the workshop presentation from Slideshare. We focused the majority of the session on some of the key principles underpinning AI. Several of them are based on those you can find in the text books and the valuable resources that are posted on the Appreciative Inquiry Commons. For example, what you focus on expands, Individuals give events their meaning, and words create worlds. But I also decided to highlight a question that I have yet to encounter in the AI literature – why are we programmed to pay attention to the negative aspects of a situation? (our inherent negative bias). In a nutshell this is because of the evolutionary imperative to respond rapidly to danger – the familiar fight, flight or freeze response that allowed our ancestors to survive long enough to become our ancestors. Nowadays the majority of us don’t face tigers in our daily lives but our reactive response can still be easily triggered by the paper tigers that apparently threaten us in our daily lives, such as the audiences who question us, the bosses who appraise us, the progeny who disobey us, the friends who ignore us, and even the anonymous drivers who disrespect us. I focused on our negativity bias for three reasons: Firstly, to emphasise that we shouldn’t beat ourselves up about our negative feelings - they are normal. I have always been a believer in the power of positive thinking but every silver lining has a cloud. My “positivity” has sometimes manifested itself as denial – a conscious effort to keep my subconscious mind and endocrine system in line. Denial of my own negative feelings could easily trap me in a double bind – feeling bad about some everyday thing and on top of that, feeling bad about the fact that I was feeling bad! An understanding of the evolutionary reasons for the reactive response can, at the very least, limit you to a single dose of bad feelings. Secondly, to introduce the fact that AI is not mindless happy talk, denial or problem avoidance but that it could become so if we are not careful. Every situation has positive and negative aspects. AI is about seeing the whole picture – both the positive and negative. However, the dominant paradigm in the world today reflects our negative bias (if you don’t believe me just watch any news bulletin for more than ten minutes or consult an elementary psychology textbook and search for the section on happiness); so AI trains us to look for the positive aspects of all situations, even those that could be deemed to be overwhelmingly negative. I develop this theme further in the blog postings: Appreciative Inquiry - Denial by any other name? and How I messed up my daily gratitude practice - Walking the tightrope between expressing appreciation and kidding ourselves. And finally, (and now for the good news) to set the scene for a discussion on ways in which AI and related approaches can help us to transcend our programming by exercising our “appreciative muscles”. There are many ways of doing this, the following six of which we discussed in the workshop: