The development of CPS’s participatory approach to planning, monitoring and evaluation

It has been a pleasure to be able to work with the CPS team to help them develop their planning, monitoring and evaluation (PME) practices. In November 2012 we put together a PME system for the CPS based on the Project logical framework approach and Outcome mapping (OM). OM is a participatory PME approach that explicitly acknowledges the fact that any intervention is embedded in a complex reality comprising of multiple actors and factors, only some of which are under the control of the project or programme. For more details of OM’s 12-step process you can download the Outcome Mapping Facilitation Manual. If you want something shorter, a 4-page summary of OM can be downloaded from the Outcome Mapping Learning Community.

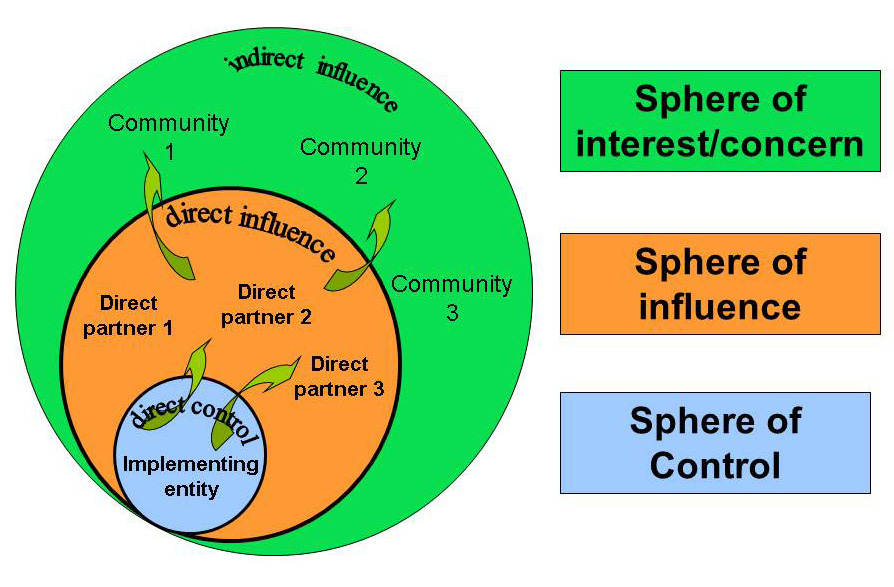

OM’s focus is on a project or programme’s direct partners in its sphere of influence (those individuals or organisations with which the programme interacts directly and anticipates opportunities for change) as opposed to its spheres of control (those who work full-time for the programme), and concern (stakeholders who are still of interest to the programme but are beyond its direct influence). OM provides the “who” in the logical sequence between activities (what the project does) and outcomes (changes to which the project contributes).

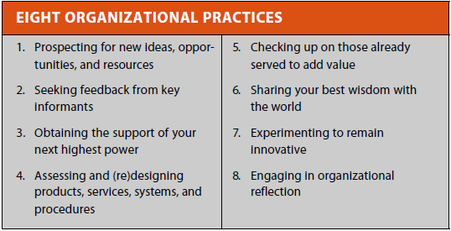

| The International development tango | Organisational Practices and the fear of sandwiches Another aspect of OM that I love is the fact that it includes a step called organisational practices. By including this step the developers of OM have made explicit the fact that the organisation is not some kind of omniscient entity that dispenses its bounty upon its chosen beneficiaries while itself remaining untouched. [a quick aside: is it just me or does the term “beneficiaries” sound a little bit patronising?]. Instead it is recognised that learning is not a one-way street and organisations need to grow and develop if they are to thrive in this ever-changing world. The OM manual lists the following eight practices that can help an organisation maintain its relevance and vitality: |

My concern was that without careful planning we could inadvertently use the eight practices as a rope of (k)nots with which to beat those in the organisation: what we are not doing to prospecting for new ideas, what we are not doing to share our best wisdom with the world, what we are not doing to remain innovative, etc. My fears may have been unjustified but my mind kept conjuring up images of the stereotypical employee performance appraisal interview. I am sure that everyone is familiar with the bitter taste left by the “compliment sandwich”, a critical comment or question between two positives, that is invariably served up on such occasions. What if there was a method of organising such reviews which ensured that the tasty bread in the sandwich was not tainted by a noxious filling while at the same time not producing something bland or sickly sweet?

Appreciative Inquiry to the rescue

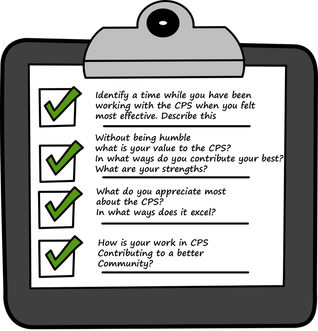

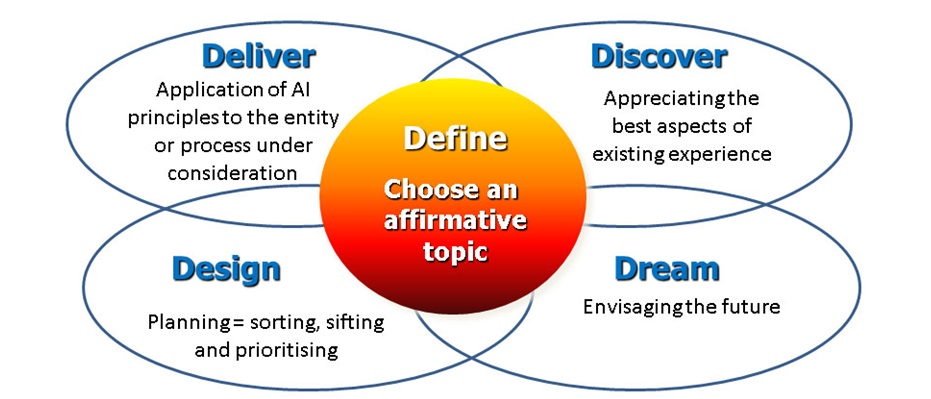

Step forward Appreciative Inquiry (AI), an organisational development paradigm that focuses on what is working to generate more of what you want instead of concentrating on what is broken in order to fix it. In our meeting in November 2012, we felt that AI could be the ideal vehicle to address CPS’s organisational practices - by building upon the already substantial strengths and achievements of the group.

The first thing to establish was whether AI was right for the CPS. This we did through a three hour workshop in which I introduced the principles of AI to the Ecological Research Unit. You can download the workshop presentation from Slideshare.

We focused the majority of the session on some of the key principles underpinning AI. Several of them are based on those you can find in the text books and the valuable resources that are posted on the Appreciative Inquiry Commons. For example, what you focus on expands, Individuals give events their meaning, and words create worlds.

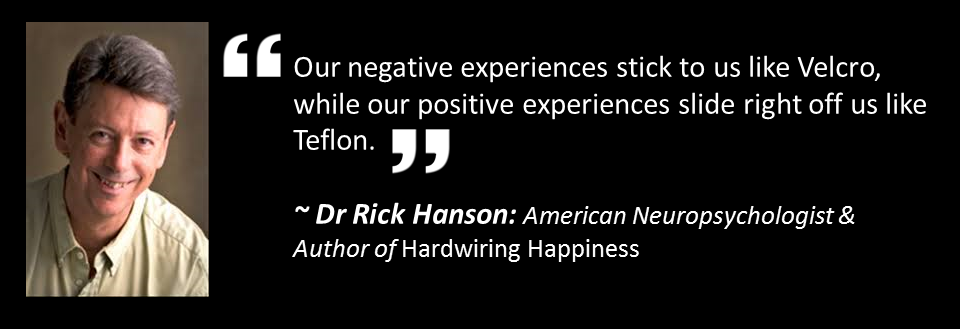

But I also decided to highlight a question that I have yet to encounter in the AI literature – why are we programmed to pay attention to the negative aspects of a situation? (our inherent negative bias). In a nutshell this is because of the evolutionary imperative to respond rapidly to danger – the familiar fight, flight or freeze response that allowed our ancestors to survive long enough to become our ancestors. Nowadays the majority of us don’t face tigers in our daily lives but our reactive response can still be easily triggered by the paper tigers that apparently threaten us in our daily lives, such as the audiences who question us, the bosses who appraise us, the progeny who disobey us, the friends who ignore us, and even the anonymous drivers who disrespect us.

Firstly, to emphasise that we shouldn’t beat ourselves up about our negative feelings - they are normal. I have always been a believer in the power of positive thinking but every silver lining has a cloud. My “positivity” has sometimes manifested itself as denial – a conscious effort to keep my subconscious mind and endocrine system in line. Denial of my own negative feelings could easily trap me in a double bind – feeling bad about some everyday thing and on top of that, feeling bad about the fact that I was feeling bad! An understanding of the evolutionary reasons for the reactive response can, at the very least, limit you to a single dose of bad feelings.

Secondly, to introduce the fact that AI is not mindless happy talk, denial or problem avoidance but that it could become so if we are not careful. Every situation has positive and negative aspects. AI is about seeing the whole picture – both the positive and negative. However, the dominant paradigm in the world today reflects our negative bias (if you don’t believe me just watch any news bulletin for more than ten minutes or consult an elementary psychology textbook and search for the section on happiness); so AI trains us to look for the positive aspects of all situations, even those that could be deemed to be overwhelmingly negative. I develop this theme further in the blog postings: Appreciative Inquiry - Denial by any other name? and How I messed up my daily gratitude practice - Walking the tightrope between expressing appreciation and kidding ourselves.

And finally, (and now for the good news) to set the scene for a discussion on ways in which AI and related approaches can help us to transcend our programming by exercising our “appreciative muscles”. There are many ways of doing this, the following six of which we discussed in the workshop:

- Practicing gratitude

- Asking appreciative questions

- Observing the feelings and thoughts that come to you

- Cultivating stillness

- Embracing uncertainty

- Being of service

The results of the fourteen interviews were summarised in this word cloud which at a glance manages to capture the essence of much of the good work that the CPS is doing.

- Exploring each other’s thoughts

- Enhancing group work and meetings in general

- Finding common ground

- Sharing our optimism

- Daring to share

- Providing a practical approaches to problem solving

- Enhancing interrelationships

- To become more positive

- Discovering the virtues and strengths of the group

- Making the best use of everybody’s strengths for the good of the group

- Delivering on our mission

- Helping the CPS to grow

- Catalysing a sustainable approach to change and change management

Barbara Smith, joint CPS Director, made an off the cuff remark that succinctly summarised the power of the AI paradigm:

“Appreciative Inquiry - It’s a mind flip”

Acknowledgement

The work was undertaken under the UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (defra) Darwin initiative project: Enhancing the relationship between people and pollinators in Eastern India (Ref: 19024) led by Barbara Smith of the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT) and Parthib Basu of the University of Calcutta.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed