1. Hesitate to encourage reflection;

2. Understand the project's ecosystem;

3. Manage in alignment with the project's ecosystem;

4. Bring in diverse perspectives;

5. Learn constantly; and

6. Embrace uncertainty

|

In the first of an eight part series of YouTube presentations on the 'humble project management toolkit' - a set of tools, approaches and philosophies which help us to effectively manage projects in the face of uncertainty, I introduce the toolkit, which contains many approaches to project planning, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation which can improve a project's efficiency and effectiveness. The toolkit's six 'compartments' are:

1. Hesitate to encourage reflection; 2. Understand the project's ecosystem; 3. Manage in alignment with the project's ecosystem; 4. Bring in diverse perspectives; 5. Learn constantly; and 6. Embrace uncertainty

0 Comments

In the fourth of an eight part series on the humble project management toolkit for better results in an uncertain world, I describe the second of two major causes of the ‘Planning Fallacy’ (why projects go over budget, over time, and fail to deliver according to specification… over and over again): - Complexity. Complexity concepts are explained using Ricardo Wilson-Grau’s ‘Fish Soup Development Story’ – why one plus one does not always equal two, and the implications of this for project management.

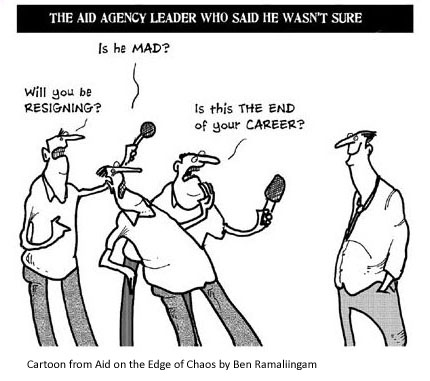

In so many spheres of life we are expected to provide definite answers rather than nuanced responses as illustrated by the bewildered response to the aid agency leader’s honest admission of uncertainty in the cartoon from Ben Ramaligam’s book. Politicians and preachers are experts in providing simple and clear solutions and this is what many people want to hear. Scientists don’t tend to talk in such a definitive manner. The nuanced tone of the scientific community is nowhere better illustrated than in the arena of climate change. 97% of climate scientists agree that climate warming trends over the past century are very likely due to human activities (emphasis added). Very likely is strong wording in the language of complexity science and I passionately feel that we should act on something that could be catastrophic in its effects and is very likely to be happening right now. However, very likely is not the same as certain and as long as there is some room for doubt there will always be people and organisations who are willing to exploit uncertainty as a basis for denial, inaction or the dissemination of deliberately misleading information. The fact is that uncertainty is the norm when addressing major questions such as how do we best combat terrorism?, how do we predict stock market performance? Is there one true God? Does God even exist? And which horse will win the 3:40 at Ascot? But our craving for certainty leaves us vulnerable to the charismatic pundits, priests and politicians who claim to have the definitive answers while we, the general public, lurch between competing certainties like some mortally wounded Shakespearian actor. So, I am going to throw my two cents into the uncertainty arena with my answer to the issue of uncertainty. There is no answer to uncertainty. Uncertainty was, is and will be with us forever so we had better learn to live with it and see it as a mystery to be embraced rather than a problem to be solved. In this blog I briefly outline why uncertainty is actually a good thing and then introduce some of the perspectives I have adopted to help me to embrace uncertainty in my everyday life. Tony Robbins identifies six conditions which must all be satisfied if we are to live a fulfilling life. He calls them the six human needs. They are:

Ideally all these needs should be satisfied but different people focus to different extents on different needs according to their personalities and the situations in which they find themselves. With regard to certainty and uncertainty, those who value certainty above all else are often known as prudent if you are focusing on the positive or control freaks if you are focusing on the downside; while those who crave uncertainty are known as daring at best and reckless at worst. In the context of Appreciative Inquiry I highlight the need to embrace uncertainty as one of six ways in which we can build our “appreciative muscles” in my blog Appreciative Inquiry and the Power of Negative Thinking. The reason I highlight the importance of this particular need is because uncertainty is ubiquitous, inevitable and increasing. The pace of change is growing with accelerating technological advances and globalisation. Slowly changing lifestyles and landscapes are becoming a thing of the past and our attitudes and behaviours need to adapt to this reality if we are to lead rounded and fulfilling lives. Here are six ways that have helped me to embrace a life of uncertainty: 1. Accept that change is inevitable and largely unpredictableA simple way to illustrate the unpredictability of the future is to contrast the consistently poor track record of pundits (those who predict specific outcomes - otherwise known as gamblers) with the healthy profits made by those who exploit this fact (those who play the odds – otherwise known as bookies). The following are a few nuggets from the plethora of famously flawed predictions made over the years. In 1876 Sir William Preece the then Chief Engineer of the British Post Office stated “The Americans have need of the telephone, but we do not. We have plenty of messenger boys.” At the time of writing there are probably as many cellphones as people on our planet… but not a commensurately huge number of messenger boys. In 1943 Thomas J. Watson the founder and long serving CEO of IBM stated “I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.” The average UK university student owned five computer or computer-like devices in 2015. In 2004 Bill Gates confidently asserted that “Spam will be a thing of the past in two years’ time.” Yet nine years later nearly 100 billion spam emails were sent... every day!!! These predictions have been cherry picked not only for fact that they were massively inaccurate but also because they were made by people who were at the top of their game in their respective fields. My objective is not to lampoon Preece, Watson and Gates but to illustrate that the much of the future is inherently unpredictable. I am sure that my predictions about telephones, computers and spam would have been no better if I had been in their shoes. Who could have predicted the fact that South Korea would now has a per capita GDP that is fourteen times higher than that of Ghana when both nation’s per capita GDP’s was $400 in 1957, the year Ghana became independent. Who could have predicted the legalisation of same-sex marriage in all 50 States of The USA by 2015 considering homosexuality was a criminal offence throughout the Union in 1961. And who could have predicted the rise of AFC Bournemouth from bankruptcy and rock bottom of the English Football League in 2008 to Premier League status in 2015. However, all of these developments, apparently impossible in foresight can be readily explained in hindsight. This fact, allied to our poor memories, the excuses we readily make for our failed predictions and the existence of the odd lucky or incredibly insightful individuals who actually make the occasional correct prediction (the punditry equivalents of lottery winners) contribute to the phenomenon known as hindsight bias which tricks us into confusing the explicability of the past with the predictability of the future. Hindsight bias is one of the reasons that we produce plans as if the future was certain and get upset when things fail to go according to plan. Planning becomes much simpler, and less frustrating, once we become aware of our poor predictive abilities in conditions of complexity. I outline ways of planning and managing projects and programmes under conditions of complexity in my Humble Project Management Toolkit talk. You can access it on YouTube but you will need a spare 45 minutes, or on SlideShare where you can scroll through it in ten minutes. The inevitability of change and its increasing rate, allied to our inability to accurately predict the future means that it is ever more important that we embrace uncertainty and do not become trapped by rigid preconceptions based on over-confident predictions of the future. 2. Develop a compelling vision_Being flexible and adaptable is not the same as being infinitely malleable and having no clear sense of direction. Despite the fact that the future is not predictable we still need to plan and have a system to help us to navigate the choppy waters through which we travel. An essential part of this navigation system is a compelling vision. There are many different and sometimes conflicting definitions of a vision. My definition (adapted from the Outcome Mapping approach to planning, monitoring and evaluation) is: A statement that reflects the large-scale changes to which you wish to contribute. It goes deeper than your personal objectives, is broader in scope, and is longer-term. The vision represents an ideal that you will support through your actions. I have a Personal Vision Statement that I periodically update in the light of experience. It can be found in my blog Being of Service: Doing well by Doing Good. Viktor Frankl, who is referred to in the opening quote, survived internship in four Nazi death camps including Auschwitz from 1942-45. His tenacious grip on life owed a great deal to his vision of humanity’s salvation through love and in love; a love he could access, even for a brief moment, when he contemplated the image of his wife. The fact that Frankl’s why helped to keep him alive and hopeful in the midst of such deprivation shows the value of a having a compelling vision through which you can find personal meaning in life, however dismal, confusing and unpredictable the circumstances may be. 3. Emphasise the journey above the destinationOur vision and objectives help to guide us but it is critical that we do not become attached to our intended outcomes above everything else. If we do so we run the risk of holding our happiness hostage to circumstances beyond our control. If we are fixated on an outcome we will tend to ignore, undervalue or marginalise unanticipated circumstances, events and outcomes as they unfold. In the words of evaluation guru Michael Quinn Patton, “being attentive along the journey is as important as, and critical to, arriving at a destination.” Most of our time will be spent on the journey and not at the destination so it is critical that we enjoy the ride or at the very least appreciate the lessons learned from the (inevitable) segments of the journey that are challenging at best and tragic at worst. This emphasis on the journey helps you to ground yourself in the present, the world as you find it rather than the world as you would like it to be. This mindful foundation empowers you to respond effectively to a constantly shifting personal and business environment. Tools to help keep you mindful along the journey include meditation (see my blogs Decoupling Runaway trains of thought and Cultivating Stillness) and a daily gratitude practice. Keeping a journal is another valuable tool. Journalling provides you with a safe place to vent. It also enhances your ability to reflect on events and reassess their meaning with the benefit of hindsight. Looking over my old journals tends to confirm H.G. Wells’s assertion that “The crisis of today is the joke of tomorrow." Journalling also helps us to recall what we did and when we did it with more precision than our memory usually permits – which can be useful when reporting to our bosses or resolving a dispute. I must confess that my journal or ‘daily log’ is very basic and restricted to the date, the event, and what category that event falls under – home, project work, football result, etc. - all entered on an Excel spreadsheet. I like to keep details of my work and home events in the same file. I also record “contextual events” such as football results and world events to provide additional hooks to assist my recall. My Excel spreadsheet is hardly evocative of the leather-bound, gilt-edged diaries of yesteryear but it works just fine for me. 4. Cultivate optimism tempered by hopeI am one of these annoying people who like to think they are a stickler for the correct terminology. If truth be told, I am a stickler for the correct use of the terminology that I am actually aware of and I have never taken much time to fathom the deep structures, rules and conventions of the English language. But I do know that the object in the wall that you plug your electric devices into is called a socket or a power point and not a plug. Perhaps I am overstating the case, but to me calling a socket a plug is analogous to calling a vagina a penis. And I wince when I hear people talk about there being less problems nowadays instead of the grammatically correct fewer problems (although I appreciate the sentiment behind the sentence in whatever way it is phrased). To be honest, these distinctions are not really important as communication is all about shared meaning. Less trivial errors are those that lead to fundamental misunderstandings that can have serious consequences. A possible example is contained in the famous sentence from the US Declaration of Independence statement as drafted by Thomas Jefferson to read “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” (emphasis added). Conventional wisdom equates the ‘pursuit’ of happiness with searching for or chasing after happiness. The implication is that you must chase after a lot of stuff in order to be happy. Taken to its extreme, the pursuit of happiness has been treated as being synonymous with the pursuit of wealth. However, there is a school of thought that believes that Jefferson was using the word ‘pursuit’ to mean an activity that you perform regularly or something you make a habit of. So if the latter interpretation is correct, Jefferson was exhorting the American people to practice happiness not to chase after it. It may seem like semantics but the implications of the two interpretations are profound. An important error, that only recently came to my attention, is the interchangeable use of the terms ‘hope’ and ‘optimism’ which could explain why optimists can be annoying while hope is often the more palatable virtue. Optimism and hope are closely related but they are not exactly the same thing. As Vaclav Havel implies, optimism is the conviction that will turn out well regardless of the situation. I happen to be an optimist of the incorrigible variety and do believe that positives can be found in even the most tragic of circumstances. However, I appreciate that not everybody thinks this and a (perhaps) more common view in the midst of difficult situations is that things could turn out well but they are not good now. There is a time dimension to this viewpoint. Things may turn out well but only after many years of struggling and, in my cosmology, many lives of hardship. Telling somebody that things are perfect when they have just lost their job, gone through a painful divorce or suffered a bereavement is not tactful and does not demonstrate a great deal of empathy. It is not surprising that people often rail against optimists because the truth is that bad things will continue to happen. If we deny this reality we risk suffocating those who are already suffering from a setback with a set of platitudes from the entire ‘Optimism Family’ – Incorrigible, Blind and Deluded. And we optimists wonder why our smiling faces are not always welcome when there’s grieving to be done, and that people turn their back on this ‘positive stuff’ when the going gets tough. Havel’s definition of hope accepts the reality that bad things will keep happening but that the resilience of the human condition can transcend these tragedies. In the words of David Henderson of the Center for Courage and Renewal “Hope will go toe-to-toe with reality because of a heart that simply refuses to quit. And there is no reality that can overcome the capacity of the human heart to withstand and even to ask boldly, Is that all you got? Is that the best you can do? My heart and the hearts of these people here with me are way bigger than that.” So while I remain an optimist, which is a valuable trait in the face of uncertainty, I strongly believe that hope should also be cultivated so that tragedy is given its proper due. 5. Abandon perfectionismI was brought up with the idea that perfectionism was a virtue. I would proudly proclaim that I was a perfectionist in job interviews, which probably explains my poor success rate in job interviews. At work I would agonise over every word in a report or every data point on a graph, checking and rechecking to ensure that I got everything right. In the meantime deadlines came and went, and by the time I finally submitted my report (which was always far from perfect in my opinion) it was often of scant value because much of its content had ceased to be relevant. As these perfectionism-related pitfalls persisted it slowly began to dawn on me perfectionism is a trap. Firstly perfection, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder and my perfect may be somebody else’s second best. Secondly perfect is not always appropriate. I found out about the 80/20 rule as applied to productivity – that 80% of your results come from 20% of your effort and the closer that you get to 100% the harder things become. And in many situations 80% or thereabouts might be good enough because the definition of quality is “fitness for purpose” not perfection. The bald truth is that perfectionists are unproductive. Despite these lessons it was still possible for me to “cheat” by working harder so that I would often go beyond ‘fit for purpose’ by putting in the ‘extra mile’ during evenings and weekends so I could (apparently) be efficient while approaching ‘perfection.’ This is not a recipe for a contented family life. I finally realised the folly of my ways when it dawned upon me that attaining perfection is an impossibility, because perfection does not actually exist beyond very narrow domains such as quizzes or examinations. I am somewhat ashamed that I was well into my fifth decade when I came to this simple but profound realisation. Having trained and practised as an evolutionary biologist I knew intellectually that natural selection does produce perfectly adapted species for many reasons including the fact that the landscape is always shifting. For example, the largest and strongest lion may be the best adapted when food is plentiful but his body size could be a handicap when food is scarce. And so it is in our work and personal lives - there are always trade-offs. Freeing yourself from the shackles of perfectionism is a way to embrace uncertainty as it liberates you from producing elaborate and excessively detailed plans when faced with complex situations though it should be used as an excuse for shoddy planning in predictable situations when a blueprint model is appropriate. 6. Don’t watch the newsCrime in England and Wales fell to a new record low in 2015, average life expectancy in Africa is at its highest levels in recorded history and worldwide it is the most peaceful time in our species’ existence (Pinker, 2011). So why does it feel like we are going to hell in a handbasket? I think that modern day news media and the fact that we consume it so uncritically bears a fair share of responsibility for this widespread perception.

Many people suggest that the news media should cover more positive stories. I agree with this perspective to some extent and pioneers like positivenews.org are helping to redress the news media’s negative bias. However, news by its very nature is sudden, dramatic and eye-catching and violent events such as a terrorist attacks, are inherently more newsworthy than incremental improvements such as the near elimination of smallpox from the planet. The understandable negative preference of the news media combined with our own negative programming (see my blog Appreciative Inquiry and the Power of Negative Thinking), and the fact that anybody with a cellphone and an Internet connection can be a news reporter helps to create an impression that we are embedded in a milieu of near-constant turmoil. The fact that most news reports concern situations over which we have very little influence contributes to our sense of insignificance. So what has all this got to do with embracing uncertainty? Many experiments have shown that willpower is a limited resource and negativity is one of the best ways to exhaust your willpower. If our senses are regularly assailed by tales of murder, disease, corruption, natural disasters and deprivation it is easily to view even day-to-day uncertainties as a source of stress against which we are impotent. And when we are short on willpower we lack creativity and resourcefulness and readily retreat into anger, apathy and cynicism. The good news is that the same global connectivity that serves up a diet of doom and despair is also a source of hope and empowerment – the story of Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani schoolgirl who stood up to the Taliban and the youngest ever Nobel Peace Laureate has spread around the world like wildfire, ideas once only available to an elite are disseminated to millions courtesy of TED Talks and people all over the world are getting access to the best teachers in the world thanks to free online learning resources. Becoming an active forager for information rather than a passive recipient helps us to achieve a resourceful state in which we can embrace uncertainty, not as something to be feared but as a source of our own empowerment. |

John MauremootooJohn Mauremootoo is a consultant with over 20 years of experience in diverse aspects of international development. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|