- “The survey is not even halfway done, yet it has already revealed a disturbing trend: immigrants are forcing old-timers out of their homes.” (Stewart 2001)

- “U.S. Can’t Handle Today’s Tide of Immigrants” (Yeh 1995)

- “Congress Threatens Wild Immigrants” (Weiner 1996)

The above snippets are carefully selected and devoid of context. As we all know, the devil can quote scripture for his own ends. I am as guilty as anybody when it comes to searching for catchy hooks and headlines to attract an audience… but we have got to be careful!

Critics can and do gleefully seize upon quotes such as these and use them as sticks to bash those who are working to mimimise the impacts of biological invasions. Banu Subramaniam (2001) argues that “the battle against exotic and alien plants is a symptom of a campaign that misplaces and displaces anxieties about economic, social, political, and cultural changes onto outsiders and foreigners.” - A serious accusation indeed, which is particularly ironic as so many of those working in the on biological invasions hold politically liberal views.

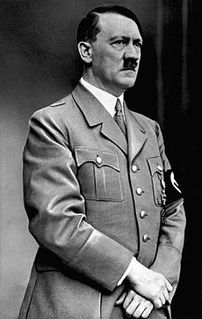

Unfortunately there have been well-documented links between the love of indigenous landscapes and extreme right wing views that we cannot bury under the carpet. Daniel Simberloff (2003) outlines this sorry history in detail, but this does not, mean that those who care about indigenous landscapes should be assumed to be racist! As Simberloff states the Nazis opposed introduced species, and that they related this agenda to their campaign to rid Germany (and perhaps the rest of the world) of people they considered foreign and inferior, need not mean that everyone who opposes introduced species does so for xenophobic, racist motives. However, muck has a nasty habit of sticking and any association with racism can only weaken the cause of those who seek to manage species introductions.

Some folks who would like to equate concern about biological invasions with xenophobia have correctly pointed out that introduced species per se are not ‘baddies’. The world’s agriculture is based on a handful of plants such as rice (native to Asia and certain parts of Africa), wheat (native to the Middle East), maize (native to the Americas) and soya (native to East Asia), all of which have been introduced beyond their native range; with massive benefits. And most introduced species do not become invasive. The ‘tens rule’ for non-native plants states that of ten per cent of introduced non-native plant species establish in the wild, and of these, ten per cent become invasive (Williamson 1993, and Williamson & Fitter 1996). This rule is far from cast-iron but the message is clear – the large majority of introduced species will not cause serious damage in their new homes.

Unfortunately, it is very difficult to predict which species will become invasive in what situation. And the stakes are very high as it is much more difficult to control a species once it has established than to keep it out in the first place. Although invasion risks are usually low, the potential impacts are high. Hence invasion biologists tend to advocate a precautionary approach to new species introductions - If in doubt keep it out! I guess this can sound pretty xenophobic if you don’t know the full story!

The flip side of this is that not all native species are ‘goodies’. Native species can become invasive too. You can be sure that a farmer in Senegal who has lost an entire sorghum crop to native desert locusts or a cattle herder in Nigeria whose land has been rendered useless by native bracken fern does not care where these species hail from. Invasion biologists focus on introduced species for very good reasons (see my posting on Red Herring #3 for an explanation). But, in our well-intentioned efforts to keep out suspected baddies we may neglect the “enemy within” and underplay the potential invasiveness of native species under certain circumstances. Thus, once again, we open ourselves to accusations of xenophobia.

Some suggestions for addressing Red Herring #4

It’s more difficult than my suggested response to Red Herring #3 (‘It’s only natural’) because the xenophobia accusation concerns several issues: Concern for introduction equates to racism; introduced species are good; and you are only worried about introduced ‘baddies’ are those I have highlighted here. My suggestions are outlined below, but I am sure that they are not the last word, given the complex nature of this particular red herring:

We need to acknowledge the fact that some individuals and groups have conflated a love of indigenous species and landscapes with racist or extreme nationalistic viewpoints. We should apologise on behalf of these people but this chequered history does not mean we should relinquish our right to care about native species and ecosystems.

We need to carefully choose our words so that they cannot be twisted to makes it appear as if we are acting from racist motives. I know many people recoil at such ‘political correctness’ but, for better or worse, we are judged on our words even if those words are stripped of their original context.

We need to make it clear that most introduced species are not problematic and we do not advocate closing the doors on future introductions. However, the precautionary principle dictates that we cannot simply introduce any species into any area without some form of risk analysis. Advocating a systematic risk analysis process is not xenophobic.

We need to acknowledge that native species can become invasive. Ultimately our concern is the balance between positive and negative impacts and not the place of origin of the species.

Last but by no means least, we must clearly communicate that our major concern is the fact that biological invasions can cause huge and unintended negative social, cultural, economic and environmental impacts. It is all about context; a species can have positive impacts in some situations and negative impacts in others. We need to embrace this complexity which cannot be dumbed down to native good, introduced bad!!

Coming up next: Red Herring #5: Aliens! What’s in A-word? – Alien means extra-terrestrial and those species you talk about evolved on planet earth.

References

Simberloff. D. (2003). Confronting introduced species: a form of xenophobia? Biological Invasions 5, 179–92.

Stewart, B. (2001). The Invasion of the Woodland Soil Snatchers. New York Times, April 24, 2001.

Subramaniam, B. (2001). The Aliens Have Landed! Reflections on the Rhetoric of Biological Invasions. Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism 2(1), 26-40. Indiana University Press.

Weiner, H. (1996). Congress threatens wild immigrants. Earth Island Journal 11, no. 4.

Williamson, M. (1993). Invaders, weeds and the risk from genetically modified organisms. Experientia, 49, 219-24.

Williamson, M. H. & A. Fitter (1996). The characters of successful invaders. Biological Conservation 78, 163-170.

Yeh, L. (1995). U.S. can’t handle today’s tide of immigrants. Christian Science Monitor 87, no. 81.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed